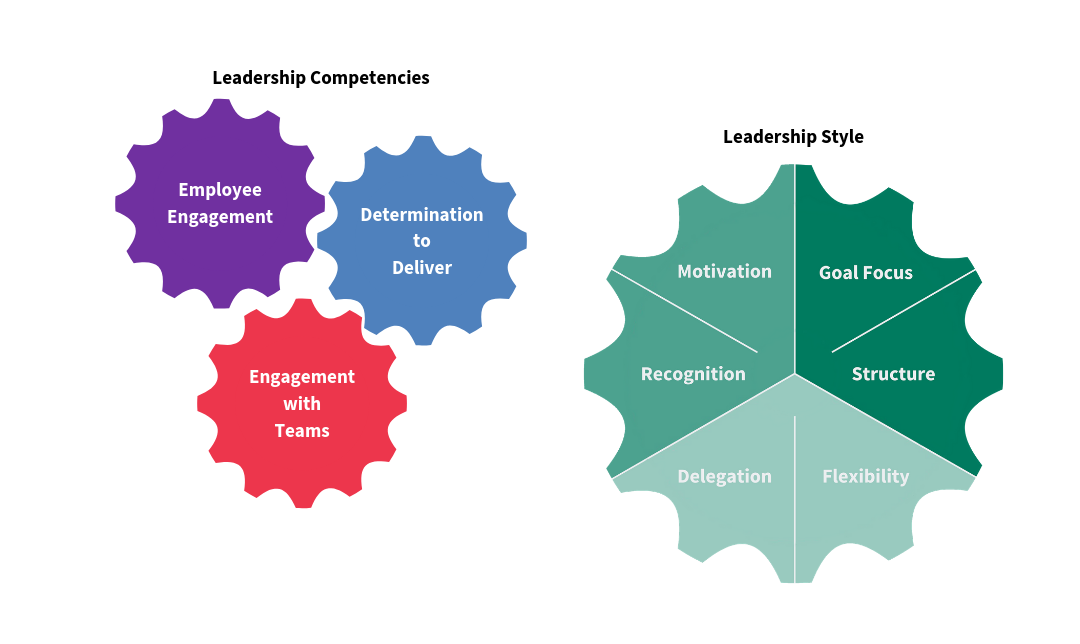

At AQR International we are known the world over for our thought leadership and pioneering work on Mental Toughness. This does lie at the core of our offering. However that offering includes other important and valuable measures, not least the Integrated Leadership Model and measure (ILM72) which is also recognised as one of the leading measures for Leadership. It assesses key leadership behaviours and the 6 aspects of Leadership Style.

More on that in a future article. The origin can be said to lie in the story below.

Much of my work in recent years has been centred on distilling my experiences and my knowledge to form them into practical activities that others can adopt and derive a benefit.

Quite deliberately, much has been carried out with the support and contribution of academic colleagues who challenge what I say and who test and evidence what I put forward.

But the starting point has always been “I have seen this work. This person did it. Can I somehow capture this and make it available to others”.

This was one of the factors that we had in mind when we first started to explore developing a Leadership Framework and Measure – the result being the ILM72

This post is longer than most. It’s the first of series which could be described loosely as “Lessons I have learned”. It describes the behaviour and approaches adopted by someone who ran a very large business and with whom I was to work very closely for 10 months.

Some 40 years ago, as a young graduate, I worked for the Wedgwood Group in a quasi – consultancy role. The brief was to go around the 20+ companies in the group carrying out projects that improved performance. It was interesting, exciting work and varied – I could easily work in 5 different companies in a week.

All were connected to Ceramics so there were common elements in each business. However, one of those businesses, Coalport China, was different in an important way. It was significantly more efficient and more profitable than any of the other businesses. The Company employed around 1200 people

The person who ran the business was also different from all the others who ran the other businesses. They were all graduates. Les Charles (not his real name), started his career in the warehouse. This distinguished him from the other CEOs.

That is interesting but it’s not the main thrust of this story. I have worked with many well-qualified people who were excellent business leaders as well as those who work their way up an organisation and were equally effective.

The group had funds for investment. After some deliberation, it was agreed that Coalport was to be given the lions share to invest in this very profitable business. Some strict conditions were applied. The budget could not be exceeded. Les also had to accept someone from head office who would oversee the project. That was to be me.

I hadn’t met him before I started the project. On day one I arrived at his office early (he was an early starter like many CEOs) and introduced myself. I asked where would my office be and Les pointed to a desk on the far side of his office. That’s where I would sit.

Clearly, he meant to keep an eye on me but this also meant I was able to watch him at close quarters. It was to prove a remarkable learning experience.

Shortly after this introduction, in came the departmental heads and managers who ran the business. This was approximately 15 minutes before the start time for almost all employees. I came to recognise this as “the daily morning meeting”. It rarely lasted more than 5 minutes and there only ever two items on the agenda. Everyone stood, no-one sat (years before Jack Welch promoted the same!).

One item was tabling of any unresolved problem or issue. Little debate was allowed. A project team was formed quickly and charged with solving the problem. They didn’t waste everyone time debating the issue. Assigning blame was forbidden.

The other item required that the managers drop index cards on the table. They were expected to note on each card anything of significance that was going on in the lives of staff in their care. This could be someone’s daughter having a baby, a financial problem, someone’s child getting to university, etc. Everyday perhaps half a dozen cards lay on the table when the managers left the room to return to their departments.

The managers were then expected to be out in their departments ensuring that everything got going promptly. They weren’t expected to return to their offices. They were expected to be visible.

This was the first point of difference. In most of the other companies, the “bosses” arrived later and the employees tended not to start work straight away at their formal start time. This lack of visibility meant time was regularly lost at the start of the working day.

At a rough guess, Coalport obtained 10-15 minutes extra contribution each day. This immediately explained some of the difference in productivity.

As we’ll see the employees were well motivated too.

Around mid-morning Les would pick up the index cards, read them quickly and following him, I found he would walk around the operations. He would stop and chat briefly with staff, usually asking them how things were going and giving them some information about the significance of the work they were doing. He was very focused on engaging with his staff.

When he entered a department where a manager had given him a card, he would seek out the person in question. The first time I saw this was someone whose son had won a place at University. The first member of the family to do so.

Les spoke to him congratulating him and his son for this achievement, asking about the course his son would study, where it was, etc. The employee was both extremely pleased and slightly embarrassed by this attention. His co-workers were equally impressed with this attention from the boss.

This was a pattern that became very familiar to me over the weeks and months ahead.

What he did next was really impressive.

Les “I suppose you have lots of forms to fill in now for grants, accommodation, etc”

Employee “Yes. I’m not used to forms. They worry me. There are lots of them”.

Les “Well don’t worry. Bring them in and we’ll sort them out. I’ll arrange for someone in accounts/admin. to help you. They fill in forms all day”.

Turning to the employee’s manager he would ask him/her to arrange that.

With that, he would move on.

Whatever the issue, he would always find a way of supporting the employee in question and it was always hugely appreciated even when the gesture was quite small.

Later he explained his philosophy. If he wasn’t interested in the challenges his staff faced, why should they be interested in his challenges. So, he spent 2-3 hours every day out of his office simply engaging with staff in this way.

Again this was in sharp contrast with some of the CEOs of other companies in the group who would rarely be seen outside of their office.

Another example was the way he engaged his staff in new product development. Most of the companies in the group employed creative people to design new products – high-value figurines, decorative pieces, etc. Mostly the new product would be introduced and employees would simply be expected to get on with it.

Les would bring the designer in and get them to sit down with representatives of the people who would create the pieces from raw clay through to dispatch. Their brief was to comment on the proposed piece and identify any problems it might present for the process.

People would point out where a feature might be easily broken, where there might be an issue with handling the piece. Inevitably the designer would rework the piece so that it not only retained its appeal but would pass safely through the manufacturing process.

The difference? The scrap rate here was minimal – especially compared to scrap rates in every other company in the group.

The bigger difference. Employees felt they owned the piece. It was theirs. They had contributed to this. They were motivated to do a great job. Les was prepared to invest time in this way and he got his return.

Not only was this an example of employee engagement but it was an example of engaging with the team – the whole team. Individual departments didn’t simply look after themselves- they worked together.

Given that much of my experience in business and organisation development until then (and still too often the case now) was to observe “silo” management in organisations and to see how difficult it was to overcome, this was one of the most impressive aspects of Les’s leadership style and behaviour.

As the project came to its end, it became challenging to finish on time and on budget.

Les shared this with his workforce. The whole workforce responded where it could – willingly and enthusiastically. By then it was their project too. The project was literally finished one day ahead of schedule and within budget …. just!

By then I had been given an assistant and both of us were swept up with the challenge. Both found ourselves working 7 days a week for the last 4 weeks of the project and often late in the evenings. Les thanked us both.

Were the employees engaged? Definitely.

Did they give their discretionary effort willingly? – without a doubt.

Was Les demonstrating highly effective leadership? You can decide. I know what I saw and think.

A week or so later I arrived home to find that Les had rung my wife and invited her and my assistants partner out for a thank you meal at a very smart restaurant. She was pretty clear that this invitation didn’t extend to me and my assistant!

The following day, we asked Les about this. His response?

“I’ve watched you handle this project and have seen how much you’ve put into this and I’ve told you many times how much I appreciate it. I’ve also watched how much you’ve got out of this and how much you’ve grown. In the last few weeks, you’ve come in every day and I have seen you enjoy that too.

However, there are two people who have had to sacrifice something and have got little out of it other than a tired but happy husband. Many wives might have made an issue of that.

I want to thank them too. I appreciate what they have given”.

Slightly bemused initially, we couldn’t but recognise what he was doing and what he was acknowledging.

The reality was that he was correct. I had learned a lot. If you look at the integrated leadership model we have developed in recent years later it’s not difficult to see evidence of that learning in that framework. It may be well-founded academically – at a very practical and operational level, it works.