The question?

The nature-nurture debate is a classic of undergraduate psychology classes. Whilst there are some significant differences on how psychologists see this continuum, it is fair to say that most think it’s a little of both.

The idea that we are fully formed from an early age is clearly not true – but much of the foundation has already been laid as we approach adulthood. Environmental events can dramatically impact on the development of personality, but in the vast majority of cases, our personality forms from the interaction of the genetic base and the environmental factors experienced.

We view Mental Toughness as a narrow personality trait. It describes how we approach events mentally (setbacks as well as opportunity). That is how we think when something occurs.

Personality was presumed, for many years, to be fixed at a very early stage of life. Often described as the “give me the child before five and I’ll give you the adult” approach. So, if you were born an extrovert, this meant you ended up as an extrovert.

Recent work has suggested that brain development is far more plastic than initially thought. Indeed, brain developmental changes can be very apparent in adolescents. Of course, this can be rather worrying when considering the duration of the Covid pandemic and the lack of developmental experiences available to many young people.

Where does this leave mental toughness?

We have some very interesting research that shows there is a definite genetic component in Mental Toughness – some children are clearly born at the tougher end of the continuum. This can be very clear to parents who often observe that two children, largely growing up in the same environment, can be worlds apart in their mental toughness scores.

Parents often feel they have somehow failed – but both sensitive and tough children can thrive and prosper, and the causes of the differences are often genetic.

Support for the genetic basis comes from a number of research papers. For example, Horsburgh et al (2009) carried out an elegant study that looked at 219 identical and non-identical twins raised apart.

They found that the identical twins – who have the same genes – had almost identical toughness scores – irrespective of upbringing. The non-identical twins – who share a birthday but not the genetic foundation – had differences in their mental toughness that would be similar to what would be expected in the general population.

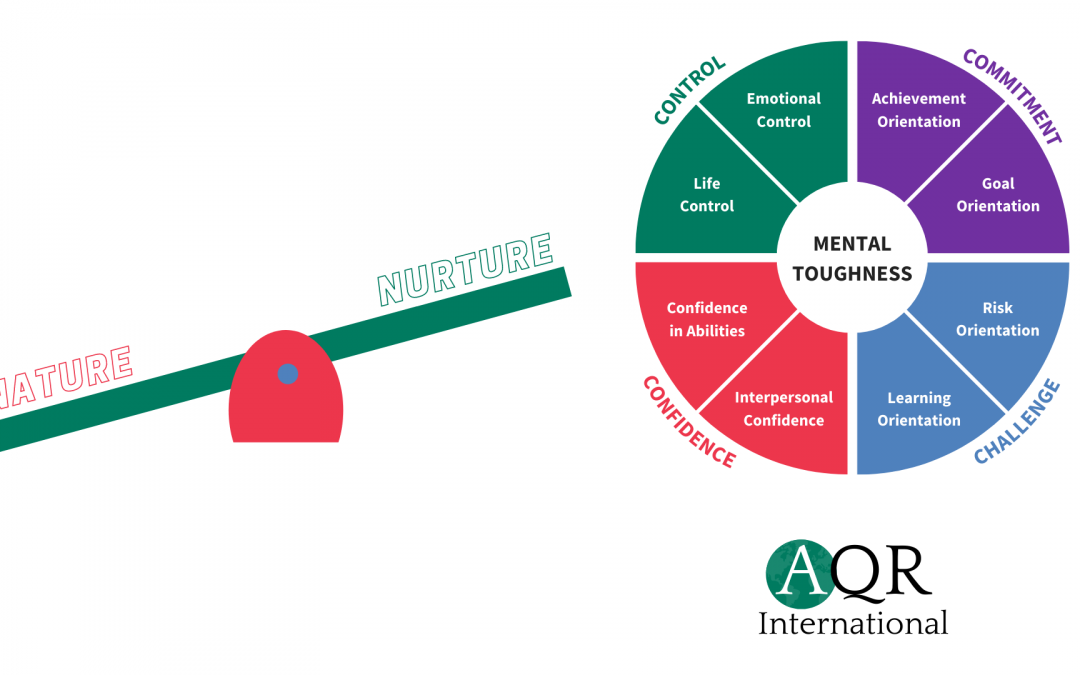

The research team then looked in more detail at the 4 ‘C’s. They reported that Confidence and Challenge were more influenced by the genetic profile, whereas Control and Commitment may be somewhat easier to develop through experiential learning.

The idea of a Confidence gene is truly fascinating and is an area that hopefully will receive much more research attention.

The figure below shows the components of the Mental Toughness concept – the constructs known as the 4Cs (Control, Commitment, Challenge and Confidence) and the 8 factors

What does this all mean?

It means that there is a different starting level of mental toughness in people. This should come as no surprise. It also suggests that intervention work early in life, up to and including the teenage years, may have an impact of the basis of mental toughness.

This is necessarily speculative, but I believe plausible. It may be easier to develop Commitment and Control, but this does mean it is possible to develop Confidence and Challenge – but we may have to work both harder and smarter at these.

So Mental Toughness might be developed – if that is what is desired and useful. It is not the solution to every challenge – behavioural or emotional – rather it seems to be a very useful trait that is linked to performance and well-being,

In addition, tools and techniques can be taught that allow more sensitive individuals to operate in ‘tough -mode’ at certain pinch points. For example, transitions at school and exams without necessarily changing their underlying toughness foundation

They might not fundamentally change the individual’s personality, rather they will allow them to have a more extensive toolkit of techniques to allow them to survive, and/or prosper, during the inevitable pinch points that occur in life.

We cannot protect our children from life’s vagaries and demands, but we can perhaps give them a psychological shield.

In conclusion

So, we can suggest that Mental Toughness is both a product of environment and genetics. The interplay between the two is complex.

Development or performance is not about throwing people ‘in at the deep end’. Rather it is about moving people gently out of their comfort zones AND providing them with the tools and techniques they need.

Experiential learning is key, but it needs to be linked with self-awareness as well as a structured and supportive plan. Really bad things happening to people does not always toughen them up. The mentally tougher may survive these, but the less tough (the mentally sensitive) may well be destroyed by them. So, it is important to take a thoughtful and nuanced approach to mental toughness development.

The MTQPlus is a very well evidenced psychometric measure that helps users to understand their mental toughness – to make the invisible, visible. If we know from where we are starting a development journey, it can be very effective.

If your interest is piqued to learn more about your own Mental Toughness profile and how to assess and develop Mental Toughness in others, please visit www.aqrinternational.co.uk and if interested in being a licensed user, contact us through the site.