Do I need to trust myself in order to trust others?

This article is a companion piece to the article examining trust from the perspective of the ‘truster’. The previous article explored the extent to which one’s mental toughness determines the extent to which they may trust others – even if those others are perfectly trustworthy.

We now examine whether, in order to trust others, we have to trust ourselves and what that might mean.

Clearly, if there is a truster there has to be someone to be trusted. Trusting someone is hard – especially when there is no objective proof that they are deserving of this. You only have to think of the spokespeople during the Covid crisis, to quickly recognise that some people appear to be more trustworthy than others, despite the fact that the fundamental message is often the same.

So, what makes someone appear trustworthy. The mental toughness model offers some insight.

On a general level, we have learned that more mentally tough individuals tend to be more ‘comfortable in their own skins’. They are fully aware of their strengths, and perhaps more importantly, their development needs.

This lack of a need to be perfect or ‘show off’ may mean that the mentally tough individual is in some ways more ‘believable’. If something is too good to be true, it probably isn’t. If someone is too good to be true, they probably aren’t. It is this authenticity that is at the heart of trust.

In general, mentally tough individuals usually have little desire to bolster their self-esteem by trying to dent that of others. This may seem a little counterintuitive – surely mentally tough individuals are keen to be in charge and perhaps show off. However, the picture is far more nuanced than this.

A mentally tough individual certainly wants to be seen and heard, but not necessarily at the cost of others’ well-being. An intriguing study in South Africa adds some substance to this argument.

The study investigated the relationship between mental toughness and trait forgiveness. It clearly emerged that mentally tougher individuals, as assessed through the MTQ, tend to have higher levels of intrinsic forgiveness.

It is hard to forgive – you have to give of yourself and not take the ‘high ground’. To do this you have to be secure and self-referent – the core of mental toughness.

Trust is, to some extent, predicated on the ability to forgive and move forward. It is based on a clear understanding that you and others are not perfect, coupled with a desire for self-development and the development of others.

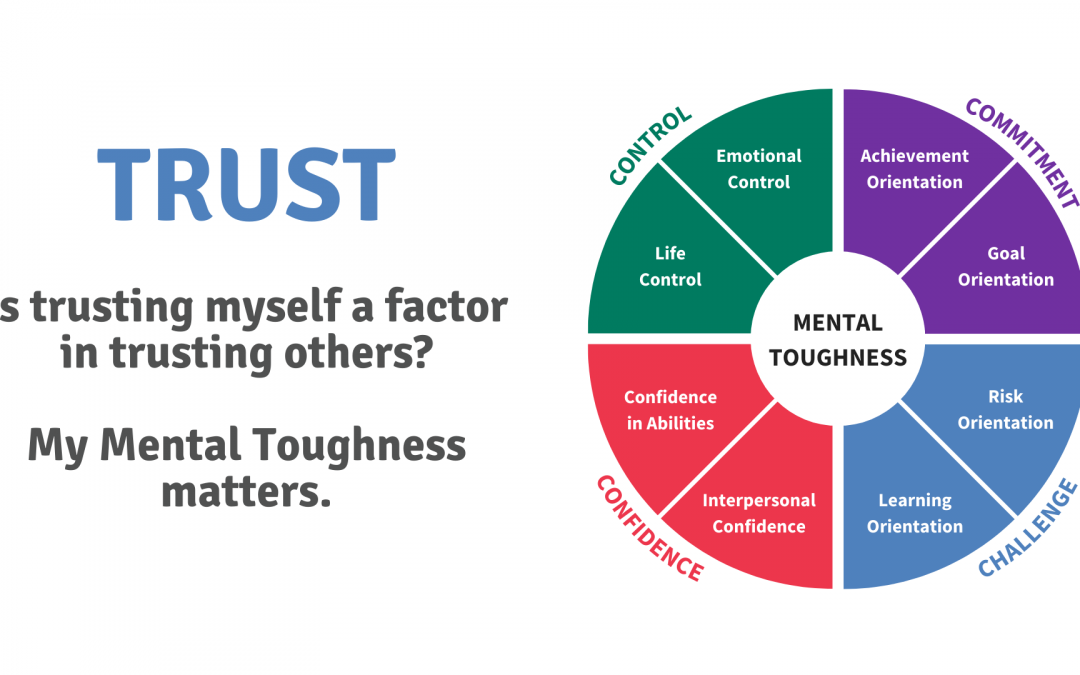

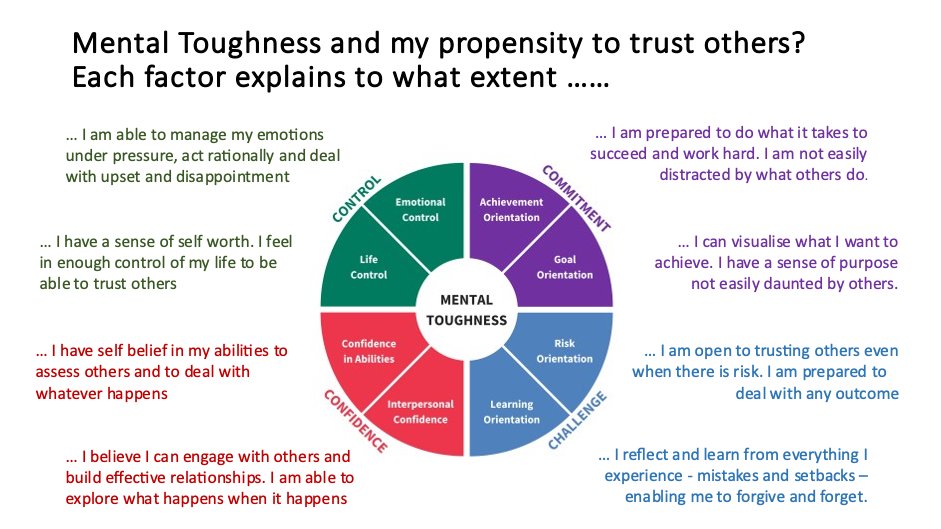

The 8-factor model of toughness allows us to beyond the general picture, allowing us to explore different types of trust and provide a more detailed answer to the question “Why am I trusted, or why I am not trusted”.

The previous article offered an insight into the 8 factors and how they might relate to trust in the trustees. These hold true for the trusted as well.

This image summarises briefly the 8-factor concept and a relationship with trust.

A good starting point when looking at the trusted is Confidence.

In the companion piece the confidence of the trusters was explored; In this article, we examine the confidence of the trusted. There is significant overlap – but some key differences.

The 8 factor model for mental toughness splits Confidence into two: Interpersonal Confidence and Confidence in Abilities.

Interpersonal Confidence is itself many-faceted, but one important aspect is being able to communicate effectively with a range of individuals. Basically, if you can talk someone’s language and use their idioms convincingly, they are more likely to listen to you and trust the message.

Confidence in Abilities is more of a fine balancing act. It is all too easy to appear smug or arrogant. The mentally tough person will normally portray their expertise authentically – neither understating nor overstating it.

Clearly, we are all drawn to trust people who appear to know what they are talking about. Faux experts on social media can be convincing but they only give one side of the argument – no ifs or buts. Messages from the mentally tough are hopefully more balanced and respectful, acknowledging the complexities of the real world, but still reaching a firm conclusion

Similarly, we can take a look at Challenge. This consists of Risk Orientation and Learning Orientation.

These closely align with the ideas and thoughts included at the beginning of this piece. It is risky to put yourself ‘out there’ in a psychologically exposed environment. Your authenticity can be a strength but also a vulnerability. In addition, people are trusted if their risk orientation is not to the detriment of the people around them.

Risk can be a positive but risking others is rather different. People trust those they believe have their best interest at heart.

Likewise, Learning Orientation is a vital foundation if you are to be trusted. It is important you learn from your success and mistakes and also you learn from the successes and failures of others.

In summary, trust is a complex phenomenon and, in practice, can be easily lost.

In a relationship, you can be both a truster and the trusted.

Self-awareness is at the heart of the trust dyad. Understanding yourself and others allows you to build trust, but you arguably need a degree of mental toughness to effectively present yourself in an authentic way.

The skills needed to trust are closely related to those needed to be trusted. An understanding of mental toughness may help people build trusted relationships and allow individuals to actively develop their trustworthiness.

For more information about Mental Toughness and its myriad applications in people and organisation development go to www.aqrinternational.co.uk or e-mail headoffice@aqr.co.uk

Professor Peter Clough Jan 2022