“Success is dependent on effort.” Sophocles

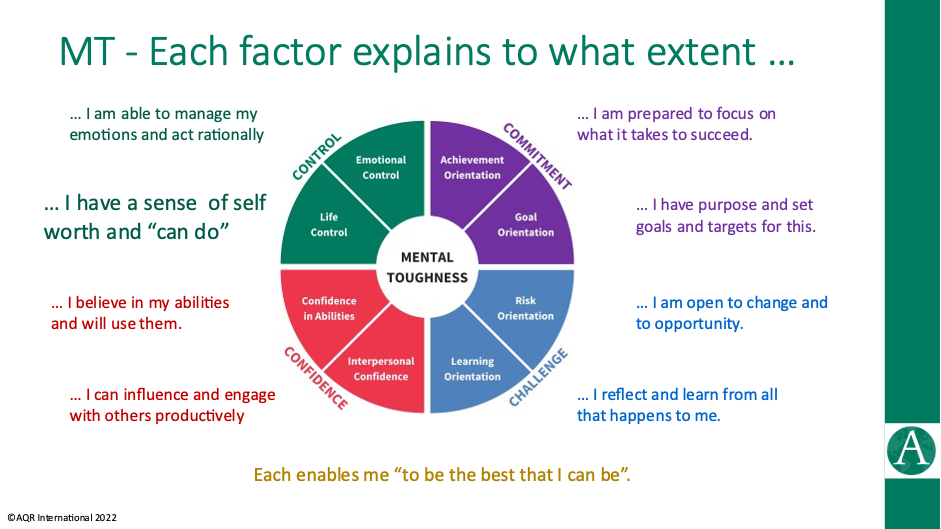

This is the fourth in a series of posts about the eight factors that form the mental toughness concept – a personality trait that describes our mental responses, how we think, to stressors, challenges and opportunities that make up our life and work experiences.

Fundamentally important, it is a major influence on our behaviour – how we act.

Achievement Orientation is one of the two factors that contribute to our overall sense of Commitment. Commitment describes the extent to which we “make promises” and the extent to which we “do what is needed to keep them”.

Achievement Orientation addresses the second part. It is perhaps intuitively the best understood of the 8 factors. Countless gurus and psychologists point to the virtue of making an effort. It has long been understood to be a factor in success and wellbeing.

Achievement Orientation describes the extent to which we are prepared to try to achieve our goals and our purpose and to keep our promises to others. Even when this is hard, uncomfortable, inconvenient and self-sacrificing (not really what we want to do right now).

Like goal orientation it reflects a form of visualisation – can we imagine what the end result looks like and what it feels like in order to create that intrinsic motivation to want to see and feel that in reality? Sports coaches commonly ask their athletes to imagine what winning looks and feels like as part of their mental preparation for events.

As with all the factors, it is possible to find two people, similar in all respects, where one can picture the desired result and is sufficiently excited to apply focus and determination to achieve it whilst the other sees the effort as disagreeable and inconvenient in some way and decides the effort is not worth the outcome.

The difference lies in their respective mental approaches. This can be significant for well-being (particularly anxiety and depression) and performance.

It can be easy to be judgemental here. This is not the point. People are simply different, and the challenge is to understand that difference and what it means for that individual and for others. The more mentally sensitive may require a degree of management and guidance but they can still fulfil a role.

This factor, like all the factors, is a spectrum with mental sensitivity at one end and mental toughness at the other. It is not a black and white idea – there are many shades in between.

And, although each factor is independent of the other, the way they can interplay will create different outcomes. There are at least 40,000 possible combinations at a base level.

So, two people, who are similar in terms of reasonable levels of Achievement Orientation, might differ in their response to tasks if one has a high level of, say, Risk Orientation (and happily tackles new and interesting projects and tasks) and the other has a low level (and prefer to avoid the new and unfamiliar because it carries threat).

This illustrates the complexity of personality, that it is nuanced and how the mental toughness concept (and the MTQPlus) measure can bring that nuance to the practitioner.

The image helps us to get an insight into this. Think about how different levels of Life Control might result in different outcomes with different levels of the other seven factors.

There is another layer of complexity to consider. All things being equal, being more mentally tough will give an advantage to the individual. But not always.

It is perfectly possible for a mentally tough person to struggle and for the more mentally sensitive to thrive. The key is self-awareness – about how they are responding in their head. Ordinarily, this is invisible which is a major challenge for the practitioner and the individual.

If self-aware of one’s level of mental toughness, one can either develop it or one can adopt practices that help to compensate for the level of sensitivity.

This is the essence of coaching. Understanding what makes you tick and what gets in the way.

How might a mentally tough achievement-orientated person struggle? They can overwork and can push others to overwork; they can burn out without recognising the warning signs; they can be taken for granted – “the reliable do-er”; they can miss doing other more important things and they can be intolerant of those less committed than them.

Of all eight factors this is the most challenging to identify positives for a more mentally sensitive person. However, they will hold back until there is a really good reason for doing something and can provide a test for the more “gung ho”.

Given this degree of nuance is true for all eight factors and that all interplay with one another, we now have a lens through which we can help people to look at themselves with all the complexity involved and understand exactly where their development needs might lie.

This illustrates that the mental toughness concept is generally about differences and not about “good or bad” or labelling people as types or colours.

There is evidence emerging that “one size fits all” interventions can do more harm than good because they are not customised.

Assessment is a challenge because the factors are invisible and any one, or combination of factors, can be the explanation for a behaviour or wellbeing outcome. Fortunately, a by-product of the considerable research behind the concept has resulted in the development of a reliable and valid psychometric measure, MTQPlus, that assesses this and the other factors with a high degree of reliability and validity.

The mental toughness concept and the MTQPlus measure represent a real advance in our understanding of individuals (and organisations). For practitioners who are engaged in developing people and organisations, understanding mental toughness goes beyond CPD. It should really be part of their armoury.

Doug Strycharczyk 2023