“I am neither clever nor especially gifted talents. I am only very, very curious.” Albert Einstein

An outcome of my mental toughness

We admire curiosity in young people and in adults. It is increasingly being spoken about as a valuable, even important quality, in individuals.

In an HBR article Dr Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Professor of Business Psychology at University College London, identified three qualities he thought essential if we are to successfully manage the complexity of modern life. The first two are intellectual acuity (aka “savvy”) and emotional intelligence. Curiosity is the third quality

It is argued that curiosity is critical to success because it indicates a hungry mind. The suggestion is that if you are inquisitive, you are open to new experiences. You can generate more original ideas and produce simple solutions to complex problems*.

It certainly should indicate an openness to experience but, of course, that might not necessarily mean this automatically translates into finding solutions. Nevertheless, this open-mindedness is the reason that individuals and organisations are beginning to value curiosity.

For the individual, it’s one way of understanding the volatile, uncertain, ambiguous, complex and fast-changing world in which we now live.

Organisations also need to survive and thrive in this changing environment. Developing and harnessing the curiosity of its people can bring a major benefit to an organisation that needs to innovate and become ever more responsive and agile.

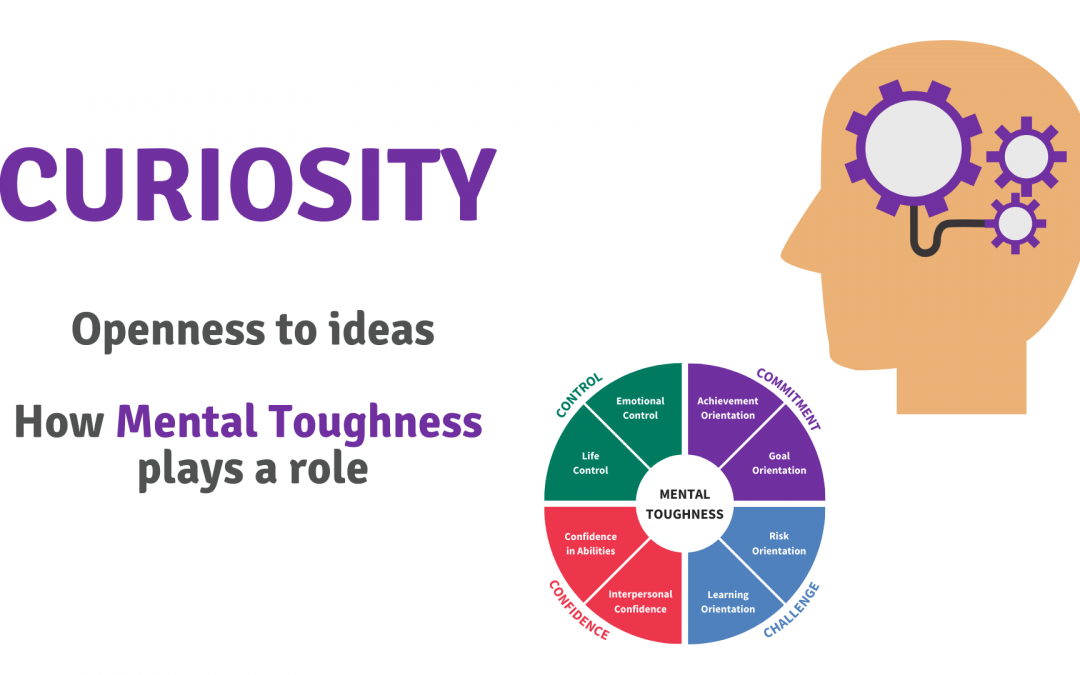

Our understanding of the 4Cs mental toughness concept, particularly in its 8-factor format provides an explanation of why that might be. Usefully, it does so in a way that can guide us to achieve solutions for the challenges we face.

What is curiosity?

First, we need to look at curiosity and define this.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as “a strong desire to know or learn something”. For some, it also means understanding how something works.

There is a little bit of complexity here.

Sometimes that curiosity is driven by need. Something doesn’t work, I need to know how to make it work.

Sometimes people don’t “need” the information they are interested in. They just want to know what is out there. The curiosity here is fuelled by desire.

There are probably many different factors that can make us inquisitive. However, we can keep this manageable by looking at two main types of curiosity:

Perceptual Curiosity – solving a problem

Where something might be bugging us and we need to find out why and sort it. It’s driven by a need to resolve something. It’s linked to problem-solving and finding out important things we should know. It’s been suggested that it is closely related to anxiety and tension. It’s how we settle our minds and deal with anxiety. Its reward is that it relieves the “itch” and sorts out the problem.

Epistemic Curiosity – just wanting to know

Epistemic curiosity is rooted in desire – you don’t need to explore what you are looking for for a specific reason. It’s exploring what is out there for its own sake. It’s what often drives inventors, academics and scientists to do what they do. There is a reward for doing it but it’s rarely tangible – it rarely involves money – more a sense of satisfaction

Thrill-seeking might be an extreme manifestation of Epistemic Curiosity. Do you seek knowledge for knowledge’s sake?

Finally, some suggest that there is a third type called diversive curiosity. It’s rarely productive. It’s common. It’s often a function of boredom. It’s what makes us look at new things like doing a google search on the phone to look up a favourite band when you could be doing something more productive. It’s akin to distraction and can be addictive. We’ll look at this further when we explore attentional control in a later article.

For the remainder of this article, we will focus primarily on Perceptual Curiosity and explore this through the lens of the 8-factor mental toughness concept. This is summarised below. This shows the 8 factors and what a significant (high) level of each factor might contribute to this type of curiosity.

The focus is on Perceptual Curiosity, which may be the form that interests individuals and organisations from a work perspective – i.e. solving problems and finding solutions. However, we will also consider Epistemic Curiosity and where there might be differences in mindset that can be explained in the Mental Toughness concept.

Starting with Life Control, to boldly explore new ideas and new settings to seek a solution or attend to a need, might require a degree of self-worth. A belief in ourselves that we “can do” this thing. Those with higher levels of Life Control are often better at prioritising and planning. Both are useful qualities in this context.

In general, when we are faced with something we need to do we can experience an emotional reaction – – fear, excitement, trepidation, anxiety, etc. Indeed, anxiety might already be a feature of the situation we are in and is one reason we are seeking a solution.

Being able to manage our emotions, Emotional Control should mean that we can control the extent to which they impact what we do, and restrict the extent to which they influence decisions made along the curiosity journey.

In terms of desire-driven curiosity, Life Control is likely to be equally important. Emotional Control might be different if elements such as excitement, joy, interest, pleasure, etc are those that propel us to examine something for the sake of it.

Given that we are considering needs-driven curiosity, it is probable that a degree of Goal Orientation will be relevant. The more goal-orientated we are, the more we have an idea of what we need to achieve. We have a sense of purpose.

Similarly, Achievement Orientation, a strong desire to attend to a need, can provide the focus and determination that drives us to whatever it takes to satisfy that need.

This could be the same for desire drive curiosity.

“Curiosity is the engine of achievement” – Sir Ken Robinson

When we come to look at the Challenge construct, this is perhaps the core of needs-driven curiosity. Discussions often centre on the two factors.

A significant level of Risk Orientation is often associated with a predisposition to see opportunities where others don’t. It also reflects a mindset where we are eager to explore new ideas, new places, new things, new experiences, etc. It’s the approach that promises to satisfy our perceptual curiosity.

We know from other work that very high levels of risk orientation can be associated with thrill-seeking. Exploring and taking risks for the sake of it – sheer nosiness. Which may be a factor in epistemic curiosity

Learning Orientation is also central to Curiosity. Reflecting on what we find, learning as we go along and using that to build knowledge, skills etc. can help the process of curiosity.

“Learning is by nature, curiosity” – Plato

Finally, Confidence is also likely to be a factor.

Curiosity of both types requires the ability to explore a situation.

If we have self-belief about those abilities, we are more likely to deploy them and be inclined to deploy them. This should support curiosity.

In the same way, curiosity will often require that we engage with people. Sometimes to find out what they know and what they can give us. Those with higher levels of Interpersonal Confidence are more likely to ask questions and worry less whether they are asking “dumb” questions. They are focused on the need to know.

It will often be that case that we need to engage with others, brainstorm ideas, use their support and guidance and top involve them in our curiosity.

In summary, we, at AQR International, are often asked if Curiosity is perhaps the fifth C in the mental toughness concept. It’s a good question because curiosity will require a degree of mental toughness to be effective.

However careful discussion, looking at the 8 factors in turn and in combination, leads us to understand that Curiosity is more of an outcome that is dependent to some extent on our mental toughness.

We define mental toughness as “a personality trait which determines, to some extent how we respond mentally to stress, pressure, opportunity and challenge”. Curiosity can be a response to and involve any combination of, or all of these.

The advantage of the 8-factor framework is that we can understand better how curiosity works in ourselves and in others.

With the application of the MTQPlus psychometric measure which assesses our level of mental toughness across each of these factors, we can identify what, within our minds, helps us or hinders us when it is useful or important to be curious about our world.

This works from an organisational perspective too. Aggregating data about the mental toughness/mental sensitivity of our people can yield a picture of the degree to which curiosity is part of our culture … and where attention for developing this might be beneficial.

*Larae Quy, Vunela