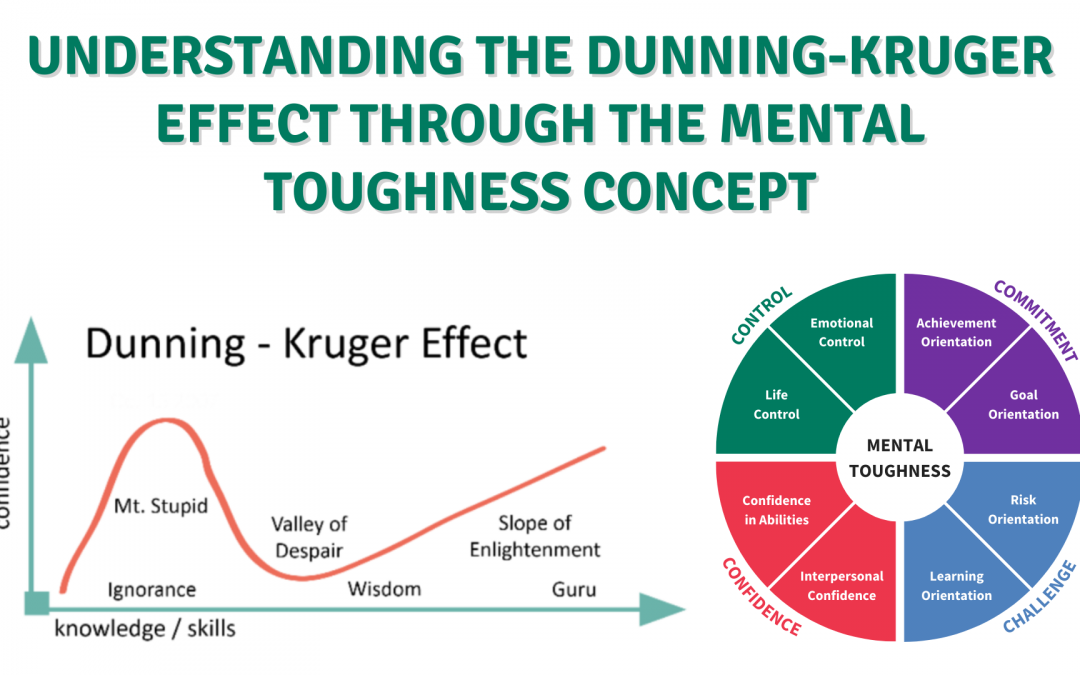

The Dunning-Kruger effect is generally described as type of cognitive bias in which people overestimate their capabilities and can imagine they are smarter than they really are. Essentially, this suggests that low ability people do not possess the skills needed to recognize their own incompetence. The combination of poor self-awareness and low cognitive ability leads them to overestimate their own capabilities.

The effect is named after researchers who first explained it – David Dunning and Justin Kruger. The term describes an issue that will be apparent to many—that some people are blind to their own ignorance.

For instance, in the original study the researchers found that, when completing measures of ability, those who achieved the lowest scores would often significantly overestimate how well they had done.

Dunning, writing in the Pacific Standard noted, “In many cases, incompetence does not leave people disoriented, perplexed, or cautious. Instead, the incompetent are often blessed with an inappropriate confidence, buoyed by something that feels to them like knowledge.”

This can have a profound impact on what people believe (however inaccurate that might be), their ability to make effective decisions and their behaviour. For example, the researchers found that, when asked to complete a Science Test, females scored equally to males. However, females would tend to underestimate their performance because they thought that males had superior scientific reasoning abilities.

This resonates to this day and reappears in many studies whether it is females tending not to opt for “masculine” professions like STEM careers or having to work harder to progress in male dominated environments.

Interestingly, its an effect that affects all of us. It is normally distributed, some of us do it a little and some of do it a lot.

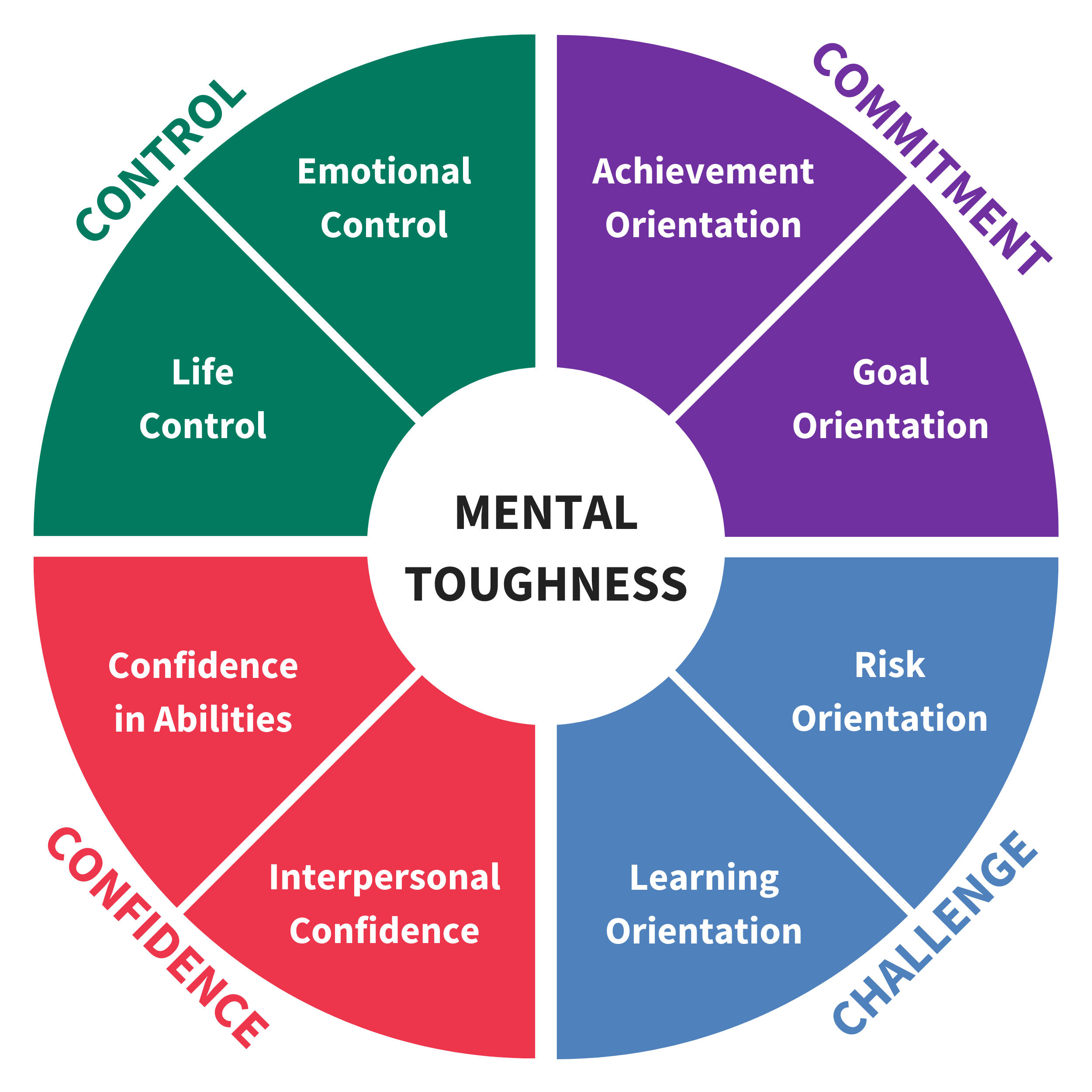

And this resonates perfectly with our work on Mental Toughness – especially our exploration with the 8-factor concept.

One of the factors is Confidence in Abilities which relates to actual abilities in interesting ways. Some of us have abilities but can still doubt ourselves and the extent to which we possess those abilities. We can also imagine others are more capable when that isn’t the case. This can prevent us from demonstrating those abilities.

Interestingly this is something we have observed in settings such as Universities and Research centres where intellectual capability would be a significant asset. If surrounded by others who are intellectually bright, it can feel that you are not as clever as they are.

Some on the other hand, as Dunning & Kruger found, can have small or moderate amounts of ability but will still believe that they have a lot of ability.

This is a factor in “how we think”. On its own it can be an issue.

The value of the 8 factor Mental Toughness concept is that we can see how the other factors can interplay with Confidence in Abilities which can magnify the issue.

A high level of Interpersonal Confidence can often mean that the individual will be sufficiently assertive to force their “half-formed ideas” on others. In some case they will use that interpersonal capability to persuade others to their point of view even when they are patently wrong. It may mitigate against listening to others. Self-belief can be so strong that you don’t believe that others have views worth considering.

Similarly, a low level of Learning Orientation might mean that the individual will think they have the ability to do things but will learn nothing when they try and will often repeat their mistakes.

Similarly, a high level of Risk Orientation might mean that the individual is tempted by new opportunities and experiences believing in their abilities to asses that risk and to deal with whatever occurs. Only to find the opposite.

The key, as ever, is one of self-awareness, reflection about the consequences of understanding yourself better and commitment to doing something about what emerges.

And that’s where the Mental Toughness framework and the Mental Toughness Questionnaires come into their own.

Both provide a reasonably comprehensive and practical way of understanding what is going on in our heads and what might be the consequences for our own effectiveness and our ability to optimise the effectiveness of others.

For more information see www.aqrinternational.co.uk or contact headoffice@aqr.co.uk