In our work around the world on individual and organisational development, the issue of Trust is very often raised in discussion. It’s a topic that matters because a lack of trust is a major impediment in most development activity.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the focus of attention is most often on the individual or group to be trusted. What are the characteristics of the trustee? What are things that an individual or organisation does or says that suggests that they can’t be trusted?

It’s a valid and useful line of thought but it can be one dimensional.

One definition of trust* – “reliance on the integrity, strength, ability, surety, etc of a person or thing” – certainly presents this idea. We can trust someone or something because ……

But what happens if these qualities are unknown (or have even been tested and to some extent found wanting). Does this mean that we cannot trust?

The Cambridge dictionary offers something slightly different. Trust is “the belief that you can trust someone or something”. Usefully it goes on to provide an illustration in the form of “to take something on trust” is “to believe something is true although you have no proof”.

Now we can see that the focus of attention is on the person doing the trusting. Trust is a belief in the probability that what you expect from a person or persons is what you will actually see or get. Trust is a mental attitude toward the notion that someone or something is reliable in the way described earlier.

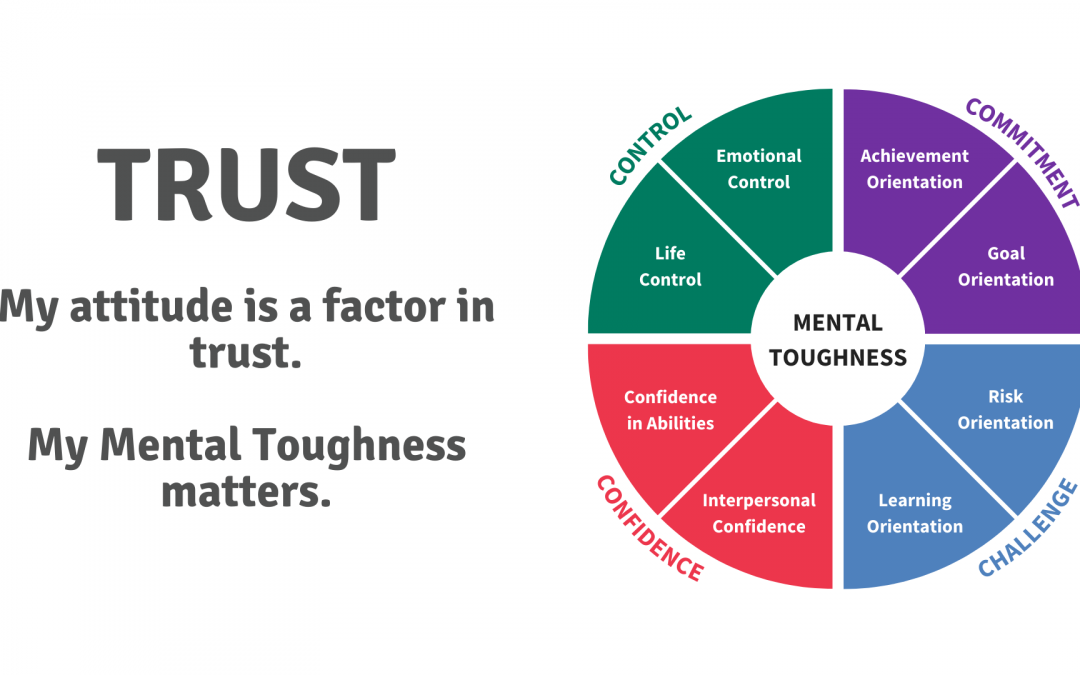

So how can mental toughness, which describes our mental attitude towards situations, shed light on our approach to trusting others?

If we know someone or something is trustworthy, there may be less of an issue to consider.

But what happens if we don’t have enough information to know that someone or something is trustworthy? Perhaps we have trusted some and they didn’t quite deliver. Can we trust them again?

This article looks at these questions and offers potential insights that can help to create a fuller picture of what trust means in practice. It needs a degree of testing.

Usefully, the development of the 8-factor concept of the 4Cs model has provided an opportunity to examine the topic of trust from a fresh perspective

If we look at the mental toughness factors, we may be able to see that our attitude towards others, and to risk in general, may influence significantly whether we trust or not. It might be possible that we fail to trust someone who is entirely trustworthy simply because of our attitude to the situation. Perhaps some are predisposed to not trust others.

Fig 1 helps to explain this

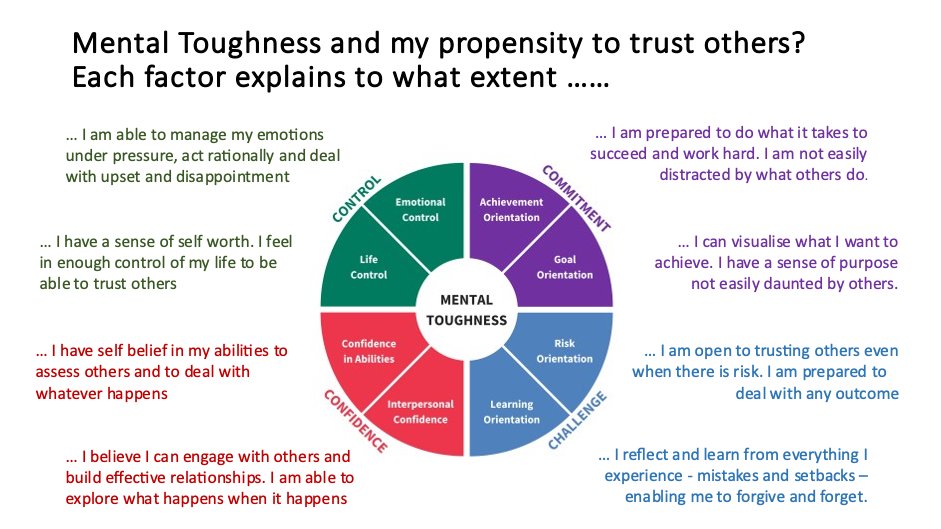

Risk Orientation might be significant. This describes the extent to which I am prepared to push boundaries, explore the unknown and whether I see the situation as carrying risk or opportunity.

If mentally sensitive, it might be that I am not so open to risk and will prefer to avoid trusting someone. A more mentally tough individual may see this differently, accepting that things might not turn out as planned or promised, but they still want to explore the opportunity and so may trust someone even though that might carry some risk.

Learning Orientation, the other aspect of the Challenge construct may also inform here. This describes the extent to which I will reflect on and learn from what happens to me and around me. It is possible that the more that this is the case, the more I might think that I have the experience to deal with a situation where trust might be tested. Indeed, I might trust another, knowing that, even it went wrong, it would still benefit me in some way.

It may have relevance in situations where a trusting relationship has not been as expected but has not been a complete disaster (perhaps for reasons not entirely in the individual’s control). I might think that I have learned from that experience and am prepared to trust the individual another time aware that I have learned something helpful from the original experience.

If I have a significant degree of Confidence in my Abilities and in my Interpersonal Confidence, I could have the self-belief to think that I can deal with a situation however it turns out. Its possible that this would increase the propensity to trust others, in the knowledge that you can deal with any negative outcome should that arise.

A significant degree of Interpersonal Confidence might also enable me to engage with others both to explore their trustworthiness and to deal with people issues that can arise.

The sense of Control, might also influence things. With Life Control, the more that someone has a sense of self-worth and will “have a go”, perhaps the more likely they are to trust someone who is involved with something in which they have a keen interest?

With Emotional Control, there is always the capacity for us to respond emotionally to events and to people – perhaps more so when trust is involved. Again, the capability to manage emotional responses and keep a cool head could be a factor in selecting whether to trust or not trust another.

Commitment, perhaps, explores what I would do in a trust relationship. Relevant perhaps if my input is a factor in its success.

In summary, if Trust is “the belief that you can trust someone or something” especially when we have little or no proof that another can be trusted, then our mental approach surely is a significant factor.

Perhaps when we are thinking about trusting another, it’s useful to start with me.

Our mental toughness, especially our self-awareness about our mental toughness matters. The AQR International 8 factor concept and the associated measure – the MTQPlus – can contribute significantly to that understanding.

For more information about Mental Toughness and its myriad applications in people and organisation development go to www.aqrinternational.co.uk or e-mail headoffice@aqr.co.uk

The next post in this series addresses the issue of Trust from another perspective – Whether or not you view yourself as trustworthy. If you do, you might be more willing to think other people are. The 8-factor concept helps to explore this too.