A case study on implementing a new sales strategy

The Challenge

Bona Fide was contacted by the HR function of a major Financial institution who, in implementing a new sales management model, wanted to support their District Managers (DM’s) in several key areas connected to change management. The aim was to strengthen the effectiveness of implementing the new strategy being adopted by the organization.

Diagnosis

It was agreed that all DM’s (17 in all) would complete the Mental Toughness Questionnaire (MTQ48) before the development programme.

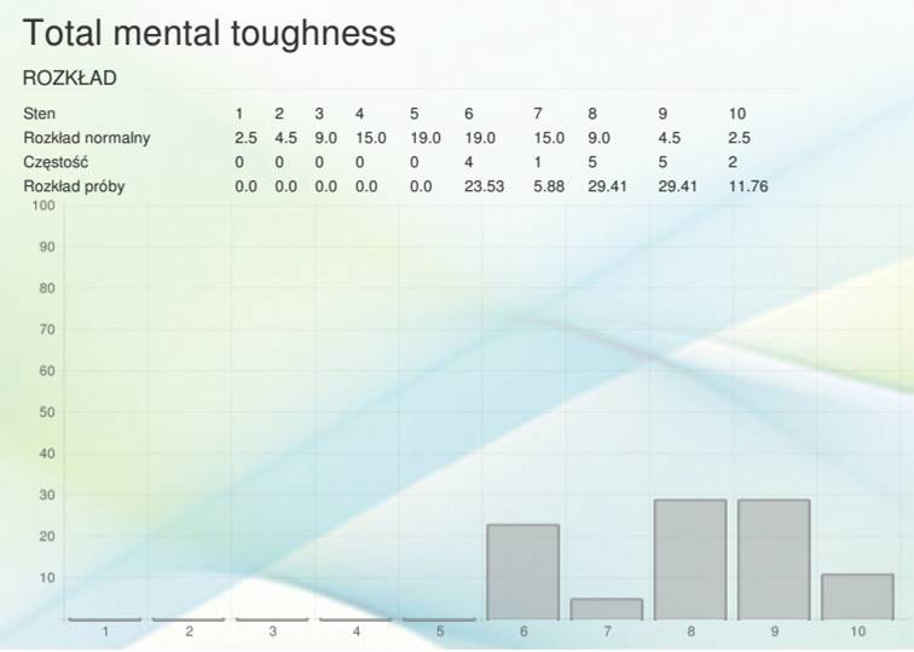

Research (e.g. AQR Int. 2008 and Merchant 2009) indicated the higher in the hierarchy the manager, the higher the level of Mental Toughness possessed by the individual. Our predictions based on casual observation of the group was that, generally, the group would achieve scores around Stens 7-8. The questionnaire’s result partially bore out this initial prediction.

Mental Toughness is defined as “a personality trait which explains to a large extent how individuals respond mentally to stressors, pressure, opportunity and challenge, irrespective of circumstances” (Strycharczyk & Clough 2021).

Research has identified that the concept consists of 4 elements – Control, Commitment, Challenge and Confidence. In turn, these are derived from 8 independent factors. These can be assessed in individuals and groups through a suite of valid and reliable psychometric measures. The MTQ48 and the MTQPlus are the two leading forms of the measure.

Figure 1. Distribution of the results of the overall mental toughness of the study group (average score for the group is Sten 8.00).

During discussion work with the DM’s we found the following:

- Some managers (generally those with the highest MTQ48 scores) tended to reject that the organisation was, indeed, making any significant changes.

- Most were not aware that it was their responsibility for implementing and promoting the new sales strategy.

- Most believed that a logical reasoned explanation, coupled with communication of the necessity for change as well as the inevitability of change, was enough to convince their subordinates of the need for change. In turn, this would make them believe that it is clearly necessary to implement and adopt the changes and make the new strategy successful.

- Most of them had little or no idea how exactly they are supposed to support their subordinates in a change process.

Analysing MTQ48 profiles for individual DM’s gave useful insights and enabled us to reach very important conclusions regarding DM attitudes towards the change their organization was facing.

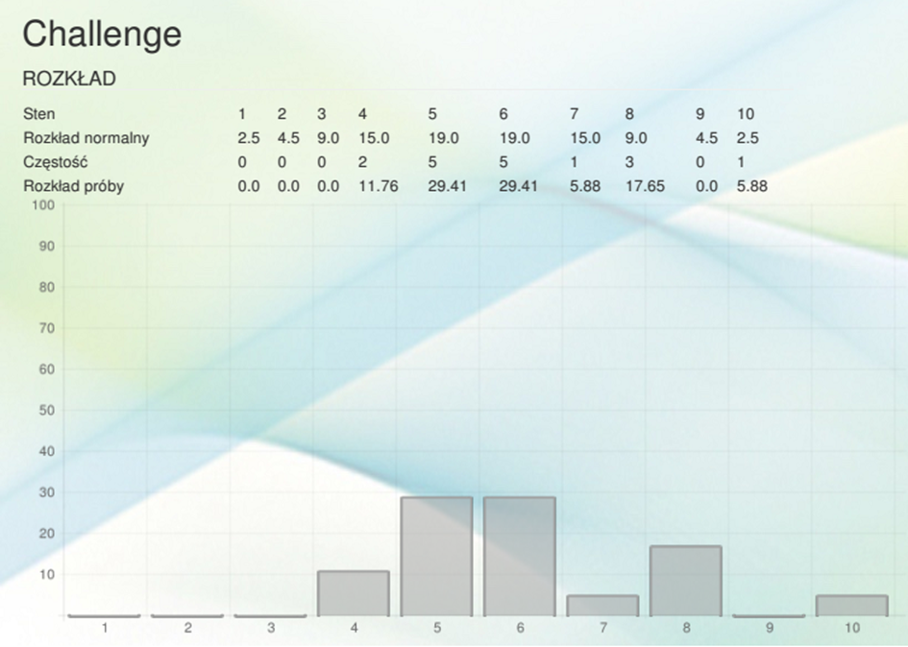

Figure 2. Distribution of mental toughness scores of the study group for the Challenge scale (average score – 6.12).

We can see that the profile for the group moved significantly to the left-hand side in comparison to overall mental toughness scores. 13 DM’s achieved lower scores on this Factor than for their overall Mental Toughness score. This was significant as most DM’s had their lowest scores on this scale which generally reflects mental approaches to change and new situations.

Two of the group with the highest scores of overall Mental Toughness as well as on the Challenge scales stated they didn’t see any important change and asked why is there so much fuss about it?

This is similar to a study carried out by AQR Int. on a large group of 97 managers in a large organization. In that case, a similar shift to the left of scores on the Challenge scale supported the observation that, even though managers were engaging in the process of the change, they were not seeing it as a significant event. The study also showed that senior managers did not really understand their role in managing change in the organisation.

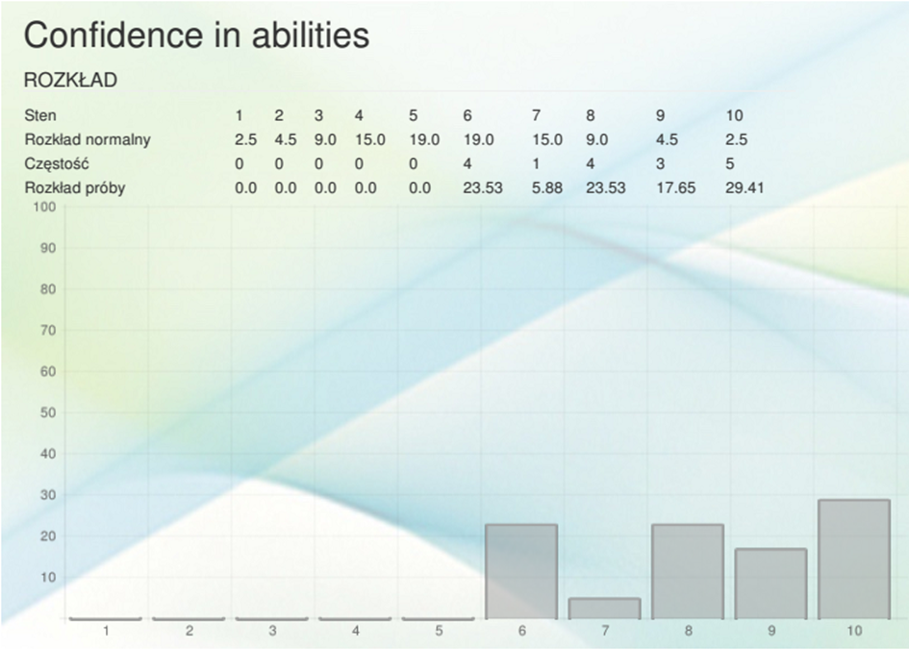

When planning the workshop which formed the core of the development activity, we also paid attention to the result achieved by the surveyed group on the Confidence scales. The overall Confidence measure for the group was 7.94. At the same time, in the “confidence in abilities” subscale, the group reached an average of 8.24 and in the subscale “interpersonal confidence” only 6.41. This is a significant difference.

Figure 3. Distribution of mental toughness scores of the study group for the Confidence in Abilities scale (average score – 8.24)

These results may, as well as indicating advantage, be the source of potential weaknesses which could undermine the effective cascading of changes in the organization. These include:

- These people may not have the skills they assign to themselves.

- They may take on too many responsibilities.

- Demonstrating extremely high self-confidence may intimidate subordinates and make them start to doubt their own skills.

- They may not tolerate or disregard the opinion of people who they think are less able or experienced than themselves.

- They may seem arrogant.

- They may be considered autocratic and cause fear to their subordinates.

- They may believe that they are right even when they are wrong.

- They may convince others they are right even when they are not.

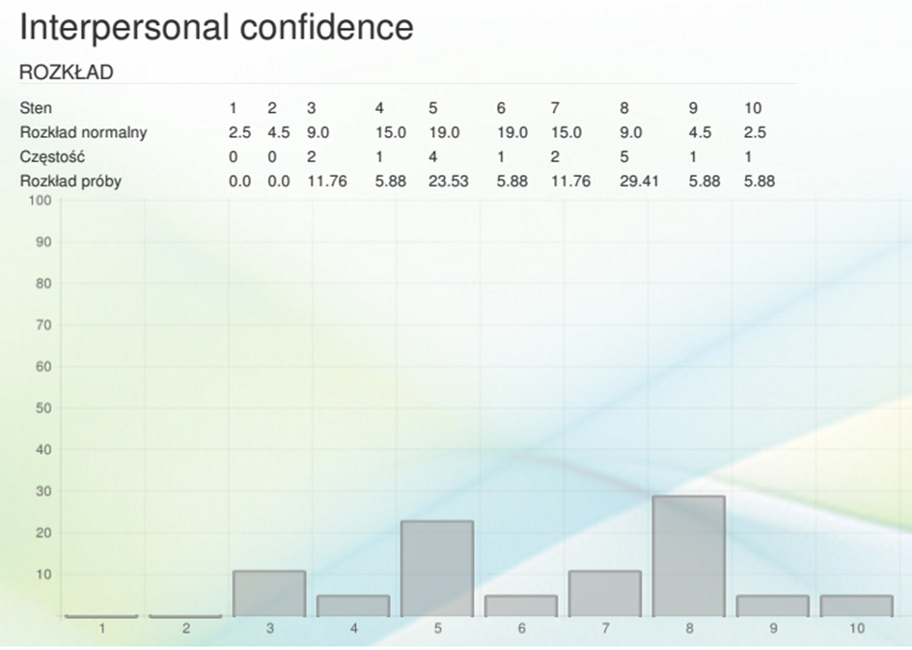

Figure 4. . Distribution of mental toughness scores of the study group for the Interpersonal Confidence scale (average score – 6.41).

There can be a risk (observed by us in other studies) that the above-mentioned potential negative consequences of high confidence in abilities may occur more often when there is a disconnect with the results of self-confidence in interpersonal relationships and in the subscale management of emotions (Emotional Control – average MTQ48 score for group 6.65).

This may translate into a management style that is directive with an extreme focus on the task, ignoring the necessity to engage with employees and staff. Additionally, this can be associated with limited flexibility for staff, strong centralization of activities and processes and underestimating the motivating importance of praise in the process of achieving goals (In our other work, we have been able to correlate this with results of ILM72 Integrated Leadership Styles Measure).

Developing a solution:

Having all this in mind, we prepared a workshop to develop more positive attitudes, during which:

During the first day:

- Participants went through the various stages of the change process through simple exercises and simulations.

- They were able to experience the whole range of feelings associated with depriving them of control over what is going on and how.

- They assessed the level of confidence in their own skills in the situation not precisely defined by the objectives.

- They experienced their own effectiveness in contexts other than those they deal with in their work.

During the second day:

With the level of group frustration already significant, in the following exercises they experienced how, still based on high mental toughness, they can approach people management differently in managing change to more effectively support the implementation of change processes in their regions.

The Outcome – a summary

Whilst the initial objective was to ‘strengthen the effectiveness of implementing the new model and strategy being adopted by the organization’, it rapidly became apparent in the initial analysis that there was:

- Resistance to change and:

- A lack of awareness of the need for change.

Furthermore, it became evident that, generally, the management style of the DM’s was not conducive to gaining ‘buy-in’ from the sales teams in a way that would motivate activity in a high-performing sales environment.

The MTQ48 assessment with feedback highlighted these limitations and allowed us to

- target interventions,

- create the awareness of the need for change and

- enable the DM’s to fully implement that change in a forward-thinking and inclusive manner.

Thus, achieving the main objective of the assignment.

For information about this case study and the mental toughness questionnaire in Poland contact www.bona-fide.com.pl

All other enquiries e-mail headoffice@aqr.co.uk or visit www.aqrinternational.co.uk

Published by

Consultant/Trainer with Bona Fide, Warsaw, Poland